By Steven Maisonet

Everybody is a modern adaptation of the 15th-century morality play Everyman. The show follows a group of five actors known as the “Somebodies,” whose roles are assigned at random by lottery each performance. On both nights this production was viewed, the character of Everybody was portrayed by Curtis Lovell.

The play centers on Everybody’s impending transition into the afterlife. Death (Lisa Ludwig), acting on orders from God (Gerald Ramsey), is tasked with bringing Everybody to their final judgment. In an early meta-theatrical twist, Ramsey, stepping outside of his role as God to appear as the show’s Usher, informs the audience that a lottery will decide which actors play which roles each night.

As the Somebodies journey into the unknown with Everybody, we meet symbolic embodiments of human experience: Friendship, Kinship (Family), Cousin, and Stuff. Each of these characters, despite their emotional weight, ultimately rejects Everybody’s plea for companionship into the afterlife.

God, portrayed with gravitas by Gerald Ramsey, is introduced through a flourish of thunder and lightning. Draped in a shimmering veil, Ramsey delivers a monologue of divine discontent, expressing the anguish of a creator forsaken by their creation. Ramsey moves seamlessly between roles—Usher, God, and back again—showcasing an impressive range and grounding the play’s themes of morality and identity. His portrayal of God is nuanced, capturing both omnipotent detachment and subtle vulnerability.

Lisa Ludwig’s Death is an unexpected delight—soft-spoken, comedic, even whimsical at times—challenging our usual perceptions of the Grim Reaper. Yet Ludwig reveals layers beneath the light-hearted exterior, asserting Death’s authority when needed. Her transformation from a docile presence to a commanding force is skillfully executed.

The central question for the Somebodies—and the audience—is “Why now?” Why must Everybody reckon with death, and what does it mean to do so? As the play unfolds, Lovell’s portrayal of Everybody grows increasingly vulnerable. They recount a prophetic, surreal dream—part vision, part confession—while navigating a landscape that blurs the line between reality and ether.

Friendship, played on night one by Gabriella McKinley and on night two by Tiger Brown, brings a lively, multifaceted presence to the stage. Both actors shine with wit and charm, though their portrayals offer distinct stylistic choices. Despite Friendship’s outward warmth, the character ultimately rejects Everybody, setting the tone for a series of poignant rejections.

Lovell’s performance is deeply empathetic. Their interactions with each symbolic character reveal layers of longing, confusion, and emotional clarity, all delivered with sensitivity and care. Lovell’s emotional elasticity anchors the production.

The play’s metatheatrical interludes are potent. In one, the Somebodies debate the racialized elements of Everybody’s dream, with Stuff questioning whether the embodiment of Friendship was cast through a biased lens. Everybody defends the dream’s authenticity, affirming the right to self-expression without censorship—a powerful commentary on identity, interpretation, and societal judgment.

Returning to the dream world, Everybody confronts Kinship and Cousin—both amusingly introduced mid-bong hit—only to be met with further deflection. A moment of absurdity arises when Cousin breaks the fourth wall, dragging a previously unseen actor, Yael Montijo Terrana, into the scene as a small child—a red herring to avoid deeper existential questioning. The cast shifts roles between nights, with Brown and Gomez trading off as Kinship and Cousin. This fluid casting emphasizes the show’s philosophical core: identity is transient and relational.

Stuff, portrayed by Rachael Jamison on night one and Gabriella McKinley on night two, is perhaps the show’s most layered character. In one performance, Stuff is playful and ironic; in another, cold and self-important. The character delivers a sobering message: our material possessions are not our legacy. The dialogue challenges us to consider how we value things over selfhood, and whether those things ultimately accompany us—or vanish with us.

Back in the “in-between” realm, tensions flare again. One of the Somebodies accuses Everybody of turning characters into “thugs,” reigniting the debate about representation. These interruptions, though jarring, highlight the play’s larger aim: to question the narratives we create about ourselves and others.

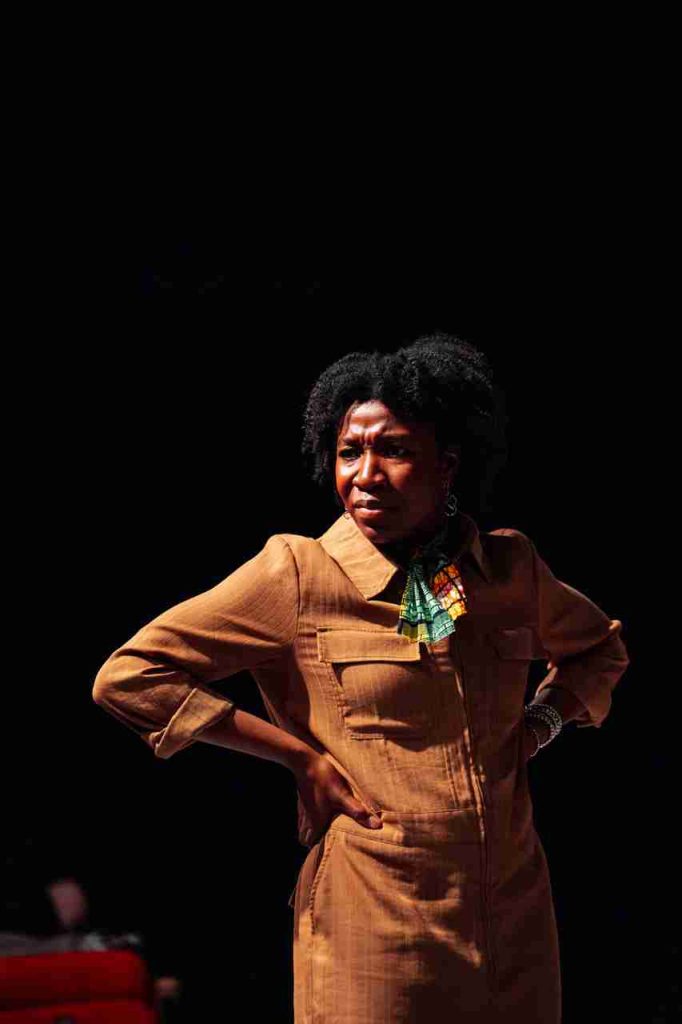

Then, a moment of brilliance: an apparent audience member stands to object to the show. The disruption feels real—until we realize she’s part of the cast. She is Love, played with radiant intensity by Dayatra Hassan. Her entrance, full of righteous anger and emotional truth, reorients the play’s direction. Hassan’s Love becomes a guiding force, leading Everybody through exercises of self-forgiveness, emotional surrender, and ultimate acceptance.

The scene crescendos into a symbolic death ritual. A voodoo-inspired dance, choreographed to Curtis Lovell’s adaptation of They Might Be Giants’ “Istanbul (Not Constantinople),” offers a moment of ancestral transcendence. It is chilling, ecstatic, and reverent—a visceral homage to those who’ve passed before.

As the story nears its end, Death reappears, scythe in hand, expecting to take Everybody alone. But Love remains. Then, surprisingly, more characters return—now reimagined as aspects of Everybody’s inner self: Understanding (Ramsey), Beauty, Senses, and Mind. These characters promise to accompany Everybody but ultimately shrink from the unknown. Only Love remains steadfast.

This production was directed by Tioga Simpson, a company member of Ujima Theatre. Simpson closes the Ujima season with a meta-theatrical performance that pushes the boundaries of form and narrative. Her distinctive directorial style—blurring the lines between performance and reality—prepares the audience not just to watch the play, but to evolve with it. The show is captured in a melodic, hypnotic rhythm that transcends the contemporary theater scene and transforms the space into something spiritual, even otherworldly. The technical direction feels intentional and precise—clearly shaped by a vision invested in provoking thought and reflection. Costuming is simple yet versatile, aesthetically pleasing in its color associations, which function well despite the actors’ nightly role changes. A strong, thoughtful vision guides the production to its powerful conclusion. Simpson’s direction marks a memorable close to the season—and hints at even more brilliance to come from this standout director.

In a final twist, Evil (Cordell Hopkins) emerges—an embodiment of everything that haunts humanity. Left on stage are Understanding, Death, and Time (Yael Montijo Terrana), watching as the cycle completes.

This production of Everybody is transcendental. It interrogates existence, legacy, and the narratives we cling to. It dismantles theatrical illusion to confront the audience with raw truth: if tomorrow were your last day, what would you bring with you?

The entire ensemble is commendable. Curtis Lovell, in particular, delivers a performance of sincerity and emotional depth. Tiger Brown brings consistent warmth and comic timing across his roles. Gabriella McKinley shines in every scene, grounding her characters with authenticity and presence. Her previous work in The Amazing Adventures of Louis de Rougemont prepared her well for the demands of this role. Alejandro Gomez’s portrayal, more restrained than in Our Lady of 121st Street, offers vulnerability and quiet strength. Rachael Jamison, a newer presence to this reviewer, is a standout—technical, precise, and commanding in every role.

Lisa Ludwig, a Buffalo theater staple and Executive Director of Shakespeare in the Park, balances her administrative prowess with a masterclass in comic acting. Her Death is funny, moving, and profound.

Finally, Gerald Ramsey’s God is a revelation. His transitions are seamless, his delivery powerful, and his presence magnetic. Only upon reviewing the script did I realize Ramsey had been performing since the very beginning of the play—proof of his subtle mastery.

Ujima is a multi-ethnic and multicultural professional theatre whose primary mission is the preservation, perpetuation, and performance of African American theatre. The company provides working opportunities for established artists as well as training experiences for aspiring ones.

Ujima Company, Inc. is located in the former School #77 on Buffalo’s West Side, at 429 Plymouth Ave., Suite 2, Buffalo, NY 14213—a location that holds special meaning for this reviewer, as it is the very building where I attended grammar and elementary school.

Consider checking out Ujima’s 2025–2026 season, which promises to be both riveting and bold. The season opens with Godspell by Stephen Schwartz on September 5th, followed by Straight White Men, The Brother Size, and Y’all Bitch, an original work by Ujima founder Lorna C. Hill.

Tickets and season passes can be purchased at the theater or online at https://www.ujimacoinc.org.